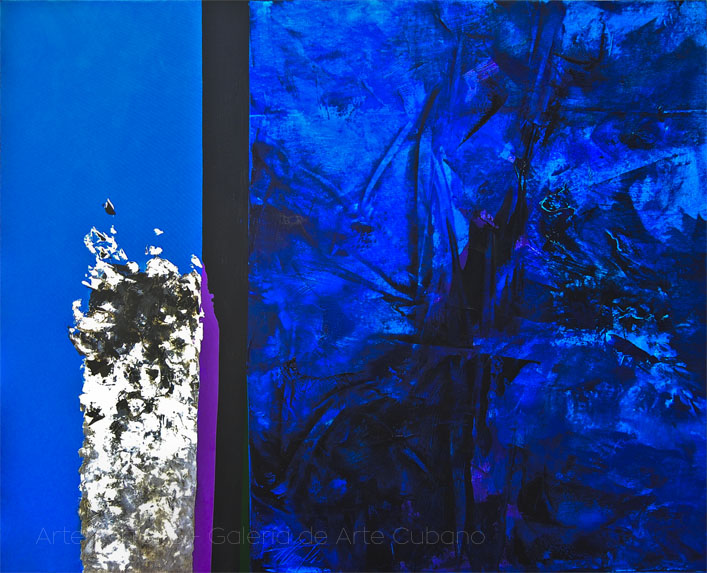

Works and Commentary to Gilberto Frometa

When Autumn Has No End

ALEX FLEITES – Poet, Curator and Art Critic –

I once wrote, “In Cuba there is no autumn, but a slow rumor that sticks to things, and a biting wind that bends the flowers.” And those old words that surely received the erosion of the Island’s salty wind come back to my mind when I review the works that make up Tropical Light, the collection of paintings with which Gilberto Frómeta wants to appear (expose himself?) before the Swiss public.

Regarding this Cuban artist, there are several things that should be fixed from the beginning if one pretends to penetrate the shimmering forest of his creation: he is a master in his craft (in both design and informalism), experimentation is one of his everyday tools, and he faces the mystery of art – that foundational moment where everything is known and at the same time forgotten – in the face of the wonder of creation – with a joy, a lack of prejudice and a passionate lack of responsibility that are hard to find in men his age.

Since he is a communicator par excellence, Frómeta does not keep his works to himself or to the greedy darkness of the market. From time to time he goes out in search of the public, both in Cuba and abroad, and surprises because of the riskiness of his proposal. He convinces us that, beyond the so-called abyss of the blank space, painting is a joy, a permanent rite of initiation, a shock and a surprise. And if not, it is not worthwhile.

While he already enjoyed fame as figurative painter earned with his expressive horses of deep human appearance1, Frómeta reacted with “disproportionate gestures”, rabid abstractions that included graphic elements, texts, combination of pigments, textures added to the canvas including vegetal fibers and whatever he found along the way. It was the difficult beginning of the 1990’s; when previously stable socialist countries were falling down and the small island of the Caribbean touched bottom in one of the worst economic and social crises of its history. He could have begun to shout. He could have gone out into the street with a poster listing his frustrations and doubts. He could have left the country and traveled to those regions where he was already well known, but instead he began to paint. And at times – what a contradiction! – the works turned out frankly optimistic. It was as if he were saying that he could only create from generosity and happiness.

Although he had already begun to experiment with informalism since 19852 in a diptych that deconstructed the emblematic figure of the horse in sunset fragments, it was the generically entitled Samples exhibition in the Pomaire Gallery in Quito, Ecuador that the painter assumed as his initiation in that field of the arts regarded by some as style, by others as sub-genre, and still by others (myself included) as art form. If we were to ask Frómeta why he reached that point in his work at such relatively late date, he would not be able to give a single answer. He says that during his learning period3 he found abstractionism alien. It should be recalled in the initial decades of the Revolution in Cuba, it was considered to be a decadent exercise, deprived of the contingences of a society dedicated to the feverish construction of a luminous future4. Although non-representational artists were not persecuted as they were in the former USSR, they did not receive any promotional benefits.

The truth is that his encounter with the work of Italian Pierpaolo Calzolari guided him to a moment of full consciousness of the painting event, not only in itself but also for itself. The “theme” or “message” would no longer be necessary (for a long period of time). The artistic gesture became self-referential, autonomous – changing from denotation to connotation.

And, naturally, the assemblage trend assumed later on bears the imprint of Antoni Tàpies, but also of Xiaobai Su, which he has absolutely no shame in admitting, since he thinks that influences nourish rather than limit; everything lies in “being capable of cooking them with your own fire”.5

It was then that the use of the airbrush, direct colors (a hint of Henri Matisse, “mentor” of his early student years), the detached, “cosmic” compositions that have been well described by Alejandro G. Alonso appeared. He fully delved into lyrical abstractionism, but with a trend where the blot is not disdainfully thrown on the surface, but “placed”, adjusted, weighed with that good design he cannot easily resist.

Let us take the case of a work like Rain. The elements, as stripes or shreds falling from above, are perfectly contained by the lines and float on top of a leaden background that clearly shows traces of condensed water. In Unexpected Love, in turn, he exploits once more the reds he took such liking to during his stay in China; he presents a blue element (an unrecognizable spatial body?) that is going to impact on that sort of magma or igneous broth not randomly, but precisely where a welcoming field opens, as in puzzles where the pieces only fit where they belong.

Pandora goes from geometry to informality; but note that the parallel line element has not remained intact – it is scorched, broken on the borders. If in a reductionist analysis of the painting we would like to consider that zone as the “rational” one, we would have to conclude that it is a chaotic rationality, in crisis, or to say the least, in a process of destruction.

It is already known that the spectator cannot avoid connecting blots with elements of the most concrete reality. Here he will “see” roots, there an insect climbing a vegetal fragment, in another piece a half moon – but none of that is real. Nor is anything else that one would like to see, because that is the case with abstraction: like jazz, it whistles a familiar tune and each one harmonizes, constructs or deconstructs the melody according to his personal history and temperament.

The titles given by Frómeta to his works appear afterwards. Initially the piece is just a visual event, not a conceptual one, and he uses the title to joke with the public; or perhaps it is a rope he throws at the public to hold on to and not be dragged completely by the explosions, the color abysses that burst and open before their surprised eyes: Mystic Flight, Rebirth , White Collar, Yellow Scream, Ardent Emotion …

In 2006 Frómeta came in contact with Asia, when he exhibited for the first time in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Symbolically, that collection is entitled Following My Own Trail, and today it may be regarded an answer to a certain critical trend that pretended to ignore the past and deny the validity of a whole generation of active artists who were accused, among other insults, of “painting to sell”, as if making a living from one’s work was not a long-cherished dream since the Renaissance.

He arrived in China for the first time in 2007. The BB Gallery welcomed him with his collection of abstract work.6 There he was also asked to prepare an exhibition of… horses! – a theme that, despite having brought him great satisfaction, he considered ended at that time. Nevertheless, he set himself the challenge.7 Again he achieved success with the public and the critics. He was in a moment of artistic fulfillment. He was able to experiment with materials that were unattainable in Cuba, and found the way to create for himself a pleasant life; a very productive and gratifying life of work that allowed him to experience an environment he had not known up to that moment. He interacted with new colleagues, shared with them knowledge and techniques, and achieved a truly professional relationship with the complex gallery circuit there.

In total, Frómeta has exhibited four times with remarkable success in the Asian giant, and a highly significant fact is that our artist lived almost five years as an equal in a country that had become a center of contemporary art, preferred in fairs and biennials and highly considered by collectors and art dealers. He went to the very center of the volcano and returned renewed from it – his faith in art as means of human enrichment intact – equipped with a lack of prejudice that makes him capable of following any road, technique or style demanded by his sensibility.

That is why the exhibition Desde mi jardín (From My Garden)8, entirely comprised of photographic manipulations of soft surreal shades, was understood by the critics not as a diversion or deviation from a long-prepared road, but as another episode of his restless temperament, another escape valve for a creative tension that is necessarily going to express itself in opposition to “isms”, falsely established hierarchies, and preconceived concepts that restrict the creative act to a series of empty explanations. Because, if indeed the cognitive function of art is in the foreground of Frómeta’s work (it is his instrument for exploring and explaining the world), it is no less true that the playful aspect plays an outstanding role in his work, since, in the end, he thinks, life is nothing but a big risky game that everyone plays with greater or lesser composure.

I have followed Frómeta’s work since 2006, when I collaborated in the creation of Abstracción sincrética (Synchretic Abstraction).9 I had already admired him for some time, but had not had the opportunity to penetrate into his Renaissance-style workshop, to see him work, to have long conversations with him about everything human and divine. And I can attest that his shield against disillusions, tricks and bad attitudes is impenetrable. He works under all circumstances, whether his work arouses enthusiastic commentaries or the critics or the market disregard him; he creates with the devotion of Byzantine icon painters and finds gratification, the greatest prize, in the work itself.

Finally, I must say once again I admire and am again disturbed by the segment of Frómeta’s work being exhibited today in Zurich. Once more I recognize his good work, his nervous pulse and his audacious devotion. I have examined his works over and over again, at different hours of the day and with various states of mind. And they not always produce the same effect on me. Those I prefer, those I would like to have in my small space in Havana, are changing. And it is because I do not succeed in “appropriating” them completely – there is always an element I missed or an artist’s gesture that now produces a new emotion in me, as if instead of observing I were the one observed. They are living beings, I say to myself; they are moved by that “slow rumor” that, in lack of a better name, we call autumn in Cuba. An autumn that, since it does not exist, since it does not reflect on the red sunsets of the Island, will also have no end.

Havana, July 2015

—

1 That part of his work is represented in the Collection of Cuban Art of the National Museum of Fine Arts in Havana.

2Pieces Ocaso 1 and Ocaso 2. Mixed on canvas, 180 x180 cm. Located at Topes de Collantes Hospital, Sancti Spíritus, Cuba.

3 He belongs to the first generation of the National School of Art, 1962-1967.

4Terms of those days.

5This text is based on numerous conversations with the artist.

6 “Light and Color”.

7Contra viento y marea (Against Wind and Tide). BB Gallery, Beijing, China., manuscript, www.pinturagfrometa.com/gilberto_frometa/?en_remarks,18

82011, Galería Orígenes, Havana.

9Collage Habana Gallery.

Alex Fleites (Caracas, Venezuela, 1954). Bachelor in Philology from the University of Havana. Poet, narrator, editor, journalist, curator and art critic. He has been editor-in-chief of the cultural page of the newspaper Rebel Youth, of the magazines Cuban Art, Union and Cuban Cinema. He is currently art director of Amnion, a Cuban poetry magazine. Among his most outstanding curatorships are Calm madness of patient color. Tribute of twenty Cuban graphics to José Luis Cuevas, University of Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico, and Live ball. Cuban painting today, an exhibition which brought together thirty masters of Cuban painting and was visited by eighty thousand people as it traveled for two years to the Colombian cities Barranquilla, Santa Marta, Cartagena, Montería and Bogotá.